I am again, as once or twice previously, in a “Just Write Something” mode.

In many ways it’s how I came into blogging itself – when wrestling with complex issues beyond the day job – writing – putting into language in any medium – is part of the thinking processes. Dialogue about it helps too. Nothing new there.

The quoted “Just Write Something” mantra is something I’ve often referred to as the key piece of advice a psychotherapist gave to Robert Pirsig, starting the recovery from his descent into institutionalised madness. The result was “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” and “Lila”. His mission was “outflanking the entire body of western thought” no less. I know how he felt.

Anyway, whatever actual piece of writing saves me from wherever “there but for grace” I might go, the jury is still out. But it’s pretty clear a comprehensive capture of “my thesis” will need to be part of the process, even though the aspirations are literary. And even though it’s on a scale where it will be impossible to dot every “i” and cross every “t” to the satisfaction of every technical critic – an occupational hazard of all multi-discipline discourse – it’s real life.

This post is itself one of the distractions – in fact “housekeeping” all the resources that contribute to the thinking behind writing is itself a distraction to the writing.

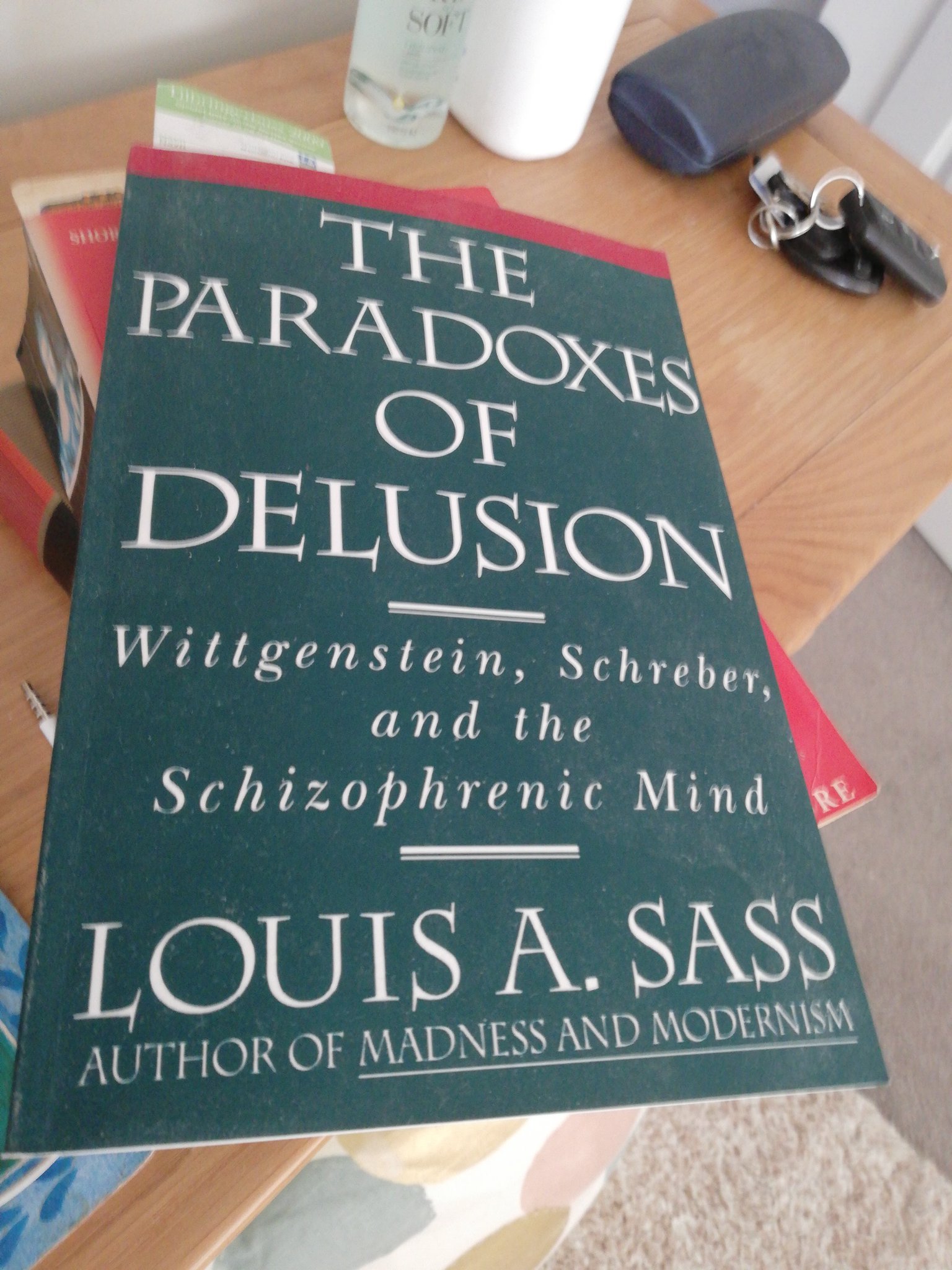

Housekeeping – literal housekeeping – has thrown-up two other relevant distractions recently. Having moved house at the end of last September, we got the office / library set-up pretty quickly, but there were quite a few archive resources still boxed-up in the garage and other hidey holes like the under-stairs and linen / airing cupboards. Anyway having got a shed up in the garden last month, we managed to shift stuff that was taking up space in the garage and … long story short, I have a few more “resources” taking up mental bandwidth in or about the office:

(1) One source of distraction is where I made the simple reference to important resources behind the “Pirsig / On Quality” post last Friday, I noticed how many of my topics went back as far as my Masters project back in 1988/91. Whilst I have a later html version of that thesis, it’s poorly formatted and has dodgy links to dumb scanned versions of the graphics and tables. The distraction was to find the original figures – in the physical archive unearthed above – and generate better future-proof versions or the graphical figures in an updated rendition of that thesis.

(2) Secondly, since making architectural / systems-thinking explicit as the default view of ALL my evolutionary thinking of the physical and psychical worlds, it has become clear my thesis is going to need a graphical language to present that thinking – networks of stuff and relations with clear semantics (noted here too.) That’s pretty close to my “day job” (eg on LinkedIn). It turns out that the semantic capabilities of my preferred language (IDEF0, for the past 3 decades) have become subsumed into standard language developments up to and including The Open Group’s ArchiMate – and there are quite a few tools that support this. One of which is “Archi” and having installed that, I’m trying to establish templates and palettes of semantic objects my thesis is going to need. Getting there.

Distractions, distractions, but resources contributing to the writing project, nevertheless 🙂

[Post Note: Oh, and I’m learning / practicing the guitar again, at least to get a few tunes to performance standard. Whether that is a distraction from or a contribution to “the writing project” we’ll see.]

Like this:

Like Loading...